When people hear about koala monitoring projects, one of the first things they often notice—and understandably worry about—is the number of deaths that occur. And yes, the numbers can seem high at first glance. But the truth is, there’s a much bigger story behind those figures—one that’s often misunderstood.

We tag and track koalas to better understand their lives, their challenges, and the threats they face. But when a koala dies during a project, people often assume the monitoring is to blame. That we’re the cause. But in reality, tagging koalas gives us the opportunity to see what’s really happening to them—things that would otherwise go unnoticed.

It’s important to remember that many of the projects we work on—such as infrastructure developments—can continue for several years, sometimes lasting through a third or even half of a koala’s natural lifespan. Statistically, it’s expected that some koalas will die during the project timeline—not because of the project, but because that’s simply life playing out.

And unfortunately, many koalas are already fighting silent battles. In some populations, more than half are affected by chlamydial disease. Many are so severely affected that, at their very first veterinary assessment, they need to be euthanased—heartbreaking decisions made for their welfare. Others seem healthy at first, only for new illnesses to emerge down the track—whether it’s progressing Chlamydia, cancers, bone marrow disease, cryptococcosis (a life-threatening fungal infection) or complex combinations of health issues.

Then there are the challenges no one can control—cyclones, flooding, prolonged rain. These severe weather events can lead to trauma and infection, especially septicaemia, and claim many lives. Predators also play a role—dingoes, pythons—and sometimes, death comes from conflict between koalas themselves, particularly during breeding season or when young koalas are dispersing to find their own territories.

And we mustn’t forget the landscape itself. Most koalas now live in heavily modified environments—suburbs, roads, backyards. They face daily risks just trying to survive in a world we’ve reshaped.

Some say we should move all the koalas out of suburbia. But others say we shouldn’t interfere at all. So what’s the answer? If we don’t tag them, we have no way of knowing what’s really happening—no way to intervene, to provide treatment, to help when help is possible. Monitoring gives us that chance. It gives us insight. It gives us a way to make a difference.

So yes—koalas do die. But their deaths are not meaningless. Each one tells us something. Each one helps us understand how to do better—for the koalas that follow.

Because at the end of the day, our goal isn’t just to count koalas. It’s to give them the best chance at surviving in a world that’s getting harder for them to navigate.

“Barnacles”, a 7-year-old male, was captured for a scheduled veterinary check-up.

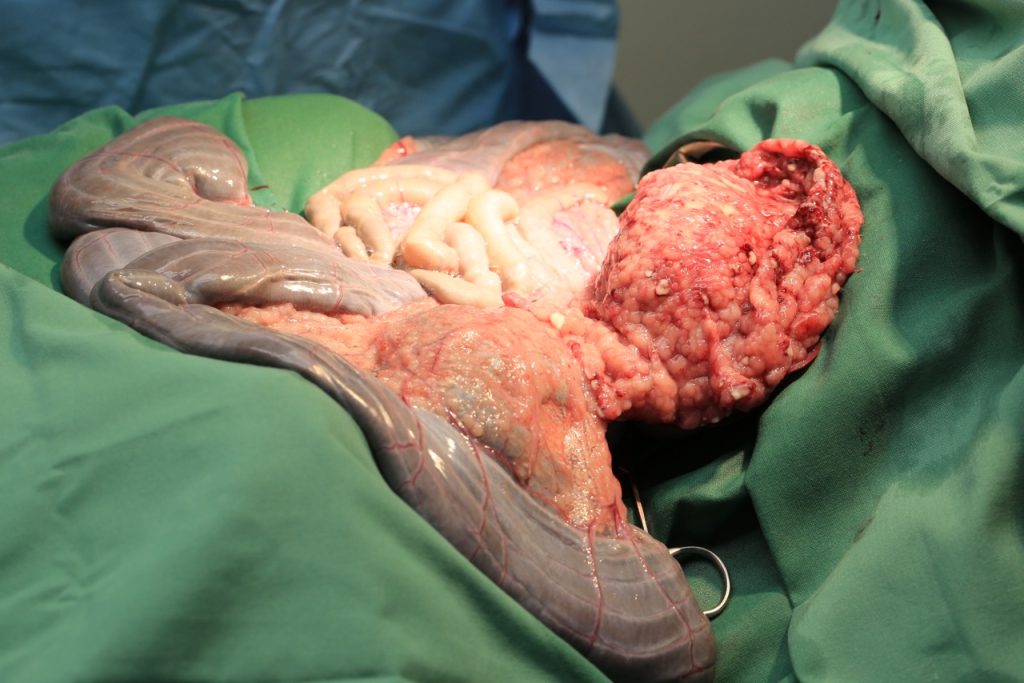

Diagnostics revealed atypical abdominal cells- an exploratory laparotomy was performed.

Surgery revealed an abdomen extensively infiltrated by tumours. Diagnosis: abdominal lymphoma.

Koala “Inara”, a 1-year-old female, was tracked and found ingested by a carpet python.

Koala “Jeremy”, a 5.5-year-old monitored male, had an osteochondroma (tumour) affecting his rib-cage (blue arrow) and extensive nodular tumours in his chest cavity at necropsy examination (right image).